Adventures In Grammatical Conundrums

As an Amazon associate, I may earn a small commission if you navigate to Amazon from my site and buy something. This will not result in an extra cost to you.

A couple weeks ago, while my friend Jane and I were having dinner at our friend Bea’s house, I happened upon an intriguing book. Honestly, Bea’s whole house is jam-packed full of interesting books, but I hadn’t seen this one before. It’s Rebel With A Clause by Ellen Jovin. I picked up the book, flipped it open enough to register that it had been signed by the author, and then started reading the introduction. Aloud. Jane tolerated this only briefly before giving me the look that suggested I’d better stop, if I know what’s good for me. I do occasionally know what’s good for me, so I stopped. But I did ask Bea about the book.

She told me that her niece-in-law bought it, stood in a line to get it signed, and then presented it at Christmas. What a fabulous gift! Both time and effort went into this one…the very best kind of Christmas present. Bea hadn’t read it yet but loaned it to me anyway. I got through it in a week. No, it doesn’t usually take me that long to read a book. But this one is full of information which deserves to be properly absorbed and appreciated, so I read at my leisure.

It’s absolutely delightful. It reminds me of a book a co-worker introduced me to many years ago, Eats, Shoots & Leaves by Lynne Truss. Both books are a delightful way to wander through the various rules of grammar, some well-understood and some not so much. In the case of Bea’s book, the premise is that the author, who has taught grammar and writing for many years, went to various locations in the States, set up a table with a sign saying GRAMMAR TABLE, and answered the questions of anyone who approached. She notes that in addition to topical suggestions such as “comma crises” and “capitalization complaints,” her sign explained that “Vent!” was also an option.

“When should you correct random strangers on their noun plurals? When you are on a grammar reality show competing for, say, ten thousand dollars’ worth of language books. Otherwise never, especially if you’re wrong. ”

What follows is a series of chapters on various grammatical topics, related in the context of conversations with complete strangers, some happy, some angry, some really quite neutral about the whole topic but dragged to the table anyway by a significant other. Told in this way, topics that some (looking at you, Jane) might consider dull or tedious become engaging. I personally love grammar and writing, and so I enjoyed every bit of this book. I even learned a few things!

I had to look up a couple words, which is always fun. “Quotidian” essentially means something that happens daily. And “floccinaucinihipilification” (which has to be said in a sort of cadence in order to get through it and I not only had to look it up, but also had to have the internet tell me how to pronounce it) means the estimation of something as being without value. It also holds the distinction of being one of the longest (non-medical) words in the English language, right up there with disestablishmentarianism.

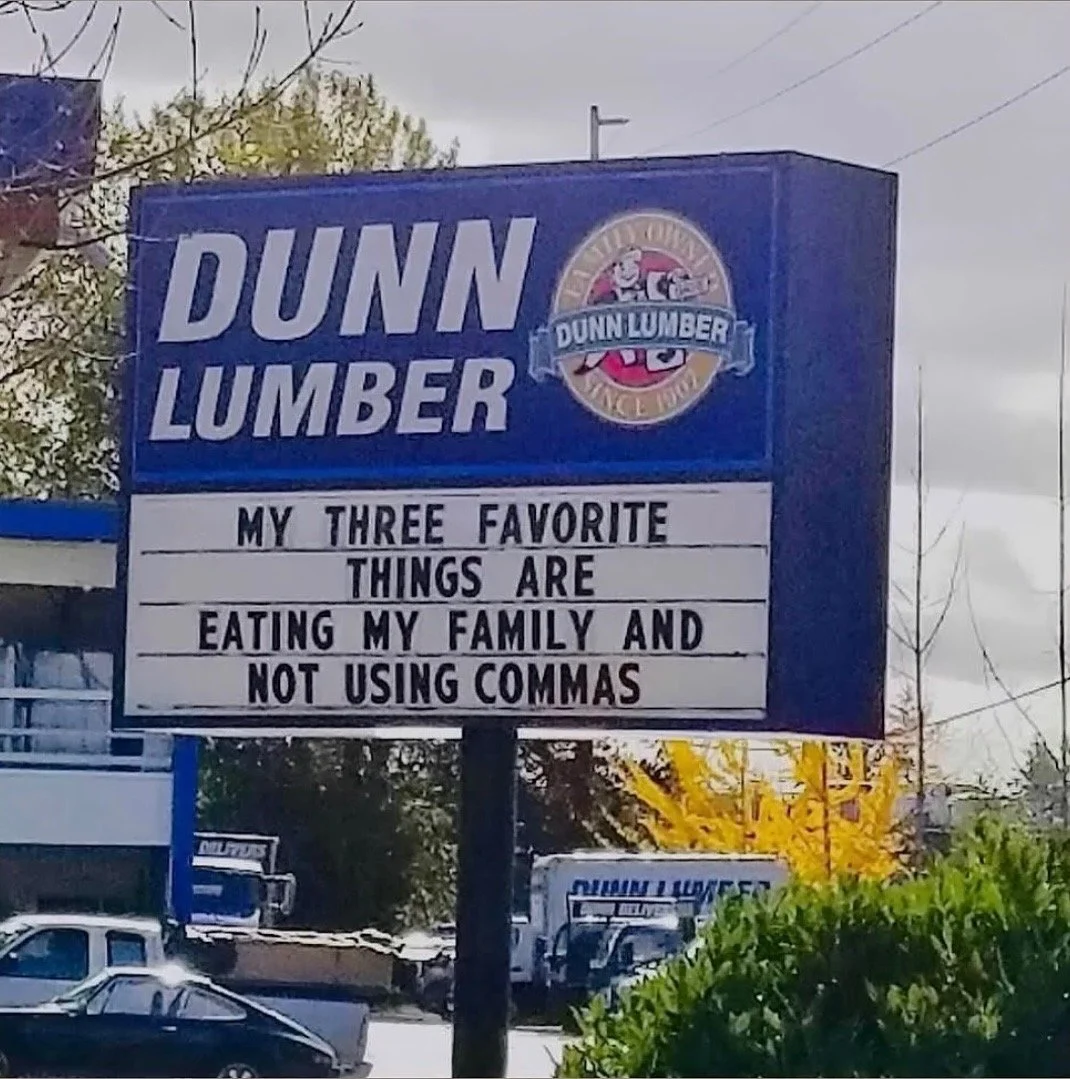

Topics of interest included the Oxford comma. I am pro-Oxford comma. Yes, I am willing to die on this hill. Commas are inexpensive and so easy to use…put in that “extra” comma (as a pro-Oxford-comma woman, I would argue that it’s not extra, but whatever) if it helps clarify the sentence even slightly. I recently wrote a review of a series by one of my favorite authors where I noted that my only criticism was the dearth of commas, which occasionally required me to read a sentence more than once to understand what the author meant. There’s really no excuse for this! Get a little comma clarity…go Oxford or go home!

The book also discusses some common errors in the usage of the pronouns I/me and who/whom. The grammatical explanation is that I and who are used when they are the subject of a sentence. Me and whom are used for the object of a sentence. If that’s too much grammar for you, try saying the whole sentence, rather than the commonly used shortened version. Examples:

My brother can run faster than me/I. Which is correct? To find out, say the whole sentence, and the answer will become clear. My brother can run faster than I can run. You wouldn’t say “me can run.”

My mother reprimanded my brother and me/I. Which is correct? Say the whole (awkward) sentence. My mother reprimanded my brother and reprimanded me. You wouldn’t say that she “reprimanded I.”

“When I recite explanations such as this one at the Grammar Table, or in my grammar classes, I often do ‘dash hands’ at the places where the dashes appear. Dash hands look a lot like jazz hands, but they are not as well known.”

One thing I had not known is that not only is there a hyphen and a dash in grammar (and they are NOT used interchangeably!), there is an in-between version. What we normally think of as a dash has two forms: the “en-dash” is used occasionally for things like time ranges (9 p.m.–2 a.m.), whereas the “em-dash” is used as regular punctuation, sometimes in place of commas. (Adventures In—a relatively new blog—is in its fourth year of publication.) I understood the distinction but I had great difficulty figuring out how to make my keyboard produce an en-dash for the explanation. And I seem to have gotten along through many years of life with just a hyphen (which essentially splits or joins words) and a dash. An em-dash, I mean. I understand how to use those two things just fine, and don’t feel poorer for not using the en-dash, although I was glad to learn the difference.

“‘It kind of goes back to maybe personality types, I think,’ said the man. ‘I never liked diagramming. My wife loves it. But she also loves to line things up on the windowsill.’”

Does punctuation go inside or outside of quotation marks? Well, in the rest of the English-speaking-world (nice use of hyphens there, if I do say so myself!), punctuation is done in a logical fashion. In American English, punctuation goes inside the quotation marks. The example cited in the book was: “My mother refers to my second cousin as “the apostrophe assassin.” Which made me laugh. And also makes the point that the period would logically fall outside the quotation marks in this particular sentence. “the apostrophe assassin”. The author doesn’t have a passionate opinion on this point, just concedes that standard American usage is inside the quotation marks, and that’s likely how it’s going to remain.

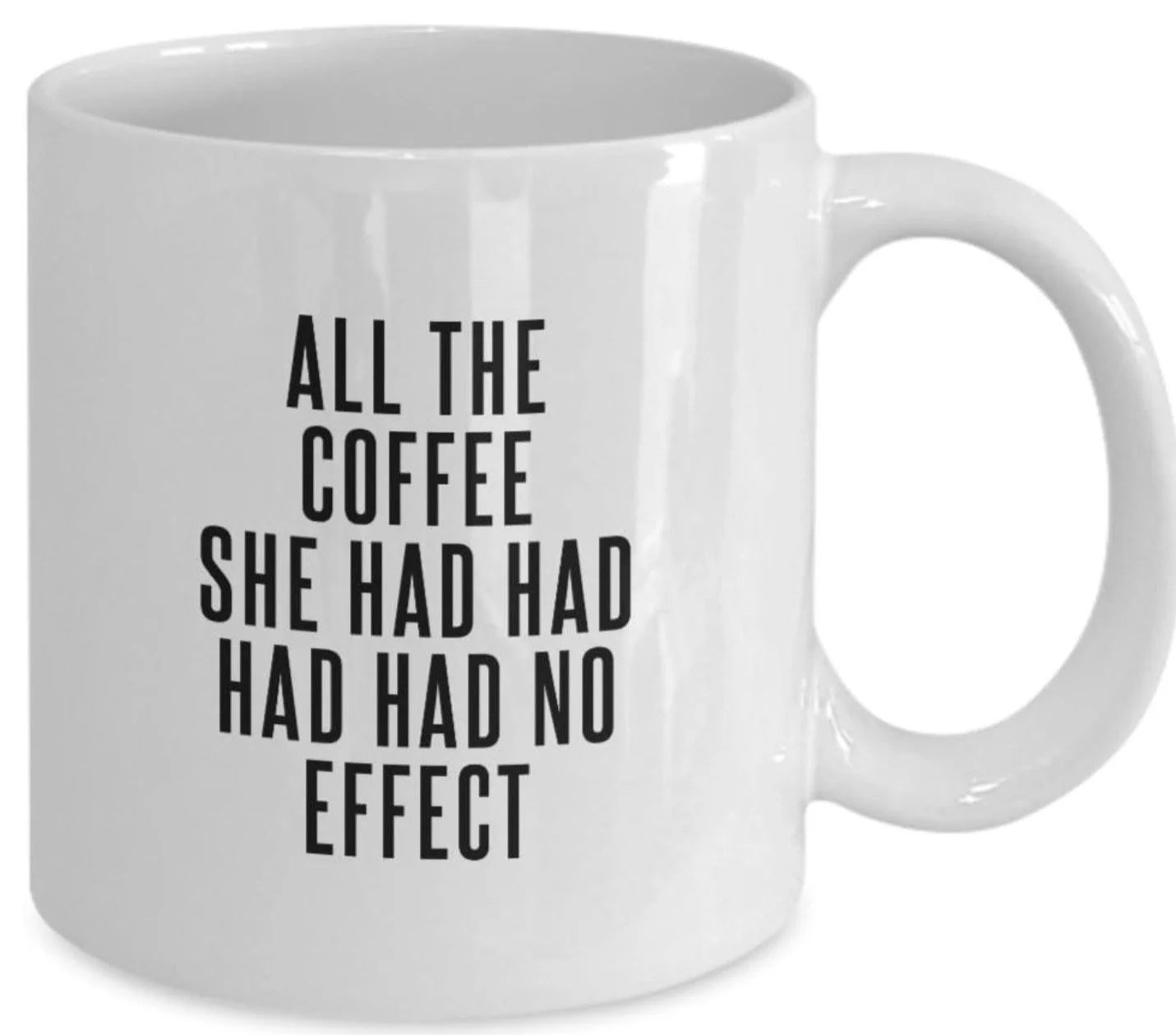

I could go on and on (and on) about this book because I loved it all. But given that it’s unlikely that everyone loves a good grammar discussion as much as I, I’ll end with one last point. Chapter 46 talks about doubled words in English, such as “had had” and “that that” and “do do.” It looks awkward when written out like that but in actual language usage, it flows so smoothly that most people use it correctly without even registering that they just doubled up words. But to make the point, here are some sentences:

All the coffee she had had no effect.

All the coffee she had had had no effect.

And for the finale…this very fine mug (which I would not object to receiving on the next gift-giving occasion, Mom):